Artificial. It’s an interesting word when you think about it. Unnatural, contrived, false or insincere are just a few possible meanings. When ‘artificial’ is used to describe something, the indication is that the ‘real’ does not exist. These are not likely words one would happily associate with education. Once the word artificial is paired with intelligence, it should be easy to see why teachers are struggling to come to terms with the implications of generative AI.

Do teachers need to know what artificial intelligence thinks about a subject? Or do they need to know what a student thinks about that same subject? The answer, of course, is obvious. What is not obvious, is how teachers are supposed to approach the increasing and inescapable problem of artificial intelligence being used in exchange what a student actually knows.

According to a report done by the Center for Democracy and Technology, 59% of teachers are certain that one or more of their students have used generative AI for school work. What does that mean exactly? Did the student have artificial intelligence do the work for them? Or did the student use artificial intelligence as a tool to better understand the subject matter they are learning? The truth is artificial intelligence can be used in both ways.

When “That’ll Teach You” first covered artificial intelligence and academic integrity back in November and talked with the Kelly Walsh High School principal, Mike Britt, he pointed out that schools need to be very careful about saying all AI use is cheating.

“I think we need to really look at what the school wide approach is going to be and not individual teachers’ approach,” said Britt. He went on to add, “What’s going to happen right away is you’re going to run into a kid that has two different teachers, and a parent that’s really upset because an assignment was considered cheating in one spot, and a resource in another spot.”

But when academic integrity is in question, artificial intelligence becomes a real problem. Who is the keeper and owner of the knowledge?

The point of education is to make the student the keeper and owner of the knowledge. Isn’t it?

So how do teachers know when their students have acquired the knowledge that was intended in any given class? The answer to that question has become much more difficult now that artificial intelligence is a player in the realm of education.

Becky Strand is an 11th grade English teacher at Kelly Walsh High School in Casper, WY and she has been teaching for 23 years. She is one of several teachers in the building who have turned back the clock before technology took over and makes her students hand-write in-class essays without the use of their laptops, cell phones or any other electronic devices. All electronic devices must be stowed away for the duration of the assignment in class.

“I always tell them that we’re not grading a computer and we’re not grading to see how the computer is doing in the class. We have to make sure that you can actually write and write well and that’s why we have to do what we do,” said Strand.

But having students hand write essays in class without any devices can’t always be the answer. In some cases, handwriting is barely legible. So, for shorter essays, this strategy might work. But what about a 5-page paper? Students don’t want to hand-write that much and teachers don’t want to struggle with the legibility for longer than a 5-paragraph essay.

One solution being suggested in an article by Kip Glazer for EducationWeek.com is to use formative and summative assessments that are plagiarism proof. This is accomplished through project based learning by focusing “on what students have learned rather than regurgitation of discrete pieces of information that they memorized.”

Project based learning, according to pblworks.org is “a teaching method in which students learn by actively engaging in real-world and personally meaningful projects.” PBL can be one solution to combat the use of generative AI for schoolwork. But it takes teachers years to accumulate the materials and develop the lessons they use in their classes. Reconstructing their lessons and assignments to fit the project based model will take a lot of time. It isn’t a quick solution. But it could be where many in education must go.

And language arts teachers are not the only teachers having to deal with AI generated material. The subject of Math is as different from English as possible, but the struggle with AI is the same.

Sara Tuomi teaches Honors Geometry, Trig-Math Analysis and Algebra 1 at Kelly Walsh High School and has been teaching for 14 years. She says artificial intelligence interference in education is nothing new to math teachers. They have been dealing with Photomath for years.

Photomath is an app that exploded onto the math scene in 2014. All a student needs to do is download the app, take a picture of the math problem on their phones and the app will solve the math problem and show the student the steps that were taken to get to the solution. On one hand it could be a great study device that helps students understand processes in math. On the other hand, it does all of the work, which a student can easily copy and turn in without learning the process for solving the problem.

This was initially a big problem for math teachers everywhere because students could simply use Photomath when working on assignments at home. Tuomi said that teachers had to place way less grading weight on homework once Photomath arrived because it is too easily accessible at home. Although it is not a school mandate, most math teachers at Kelly Walsh have their students secure their cell phones in a cell phone holder in the front of the classroom. The moment students get to class, they have to place their cellphone in the pocket assigned to them and leave it there for the duration of class. This helps thwart the usage of the app during class.

But according to Tuomi, Photomath isn’t a foolproof way for students to cheat. There are ways that teachers can tell when a student uses it.

“You can definitely tell when a kid has done it because the math language on there is definitely at a higher level and so these kids are copying things that they’ve never seen before. Using certain notations and things and you’re like, ‘well you totally copied that because I guarantee you’ve never seen that type of script before when you know we’re teaching you algebra at a very basic level,’” said Tuomi.

Tuomi added that getting kids to ask the how and why questions in math is the hardest part. They just want to write down the answer and call it good. But understanding the how and why is probably the most important skill she can teach them.

“There’s no wanting to know the how or the why really anymore and that’s what I’ve totally nerded out on the last few years is the how and the why,” said Tuomi, and she added, “I’m older now and I’m teaching and I’m like ‘oh that’s cool’ I want to know the how and the why and I try to give them that.”

And the same logic applies in English classes too. In many cases, when a student turns in AI generated content and passes it off as their own, teachers can usually spot the plagiarism relatively easily because the vocabulary is suddenly much higher than the student has shown in previous work. In these cases, an English teacher can just pick out a few words used in the paper and ask the student to tell them what those words mean on the spot. This particular strategy should help in the event that a parent challenges a teacher’s accusation on a student using AI generated work.

“I mean it sucks that we even have to have a backup plan in case we do get challenged by a parent on ‘how did you know my kid cheated?’ but that’s a really easy way to do it,” said Strand. Strand has not used this strategy yet, but she believes she will likely have to use it at some point to prove her suspicions in cases of using AI generated work to cheat.

Which brings up another current problem in the usage of AI as a cheating device. What resources do teachers have to detect AI generated content?

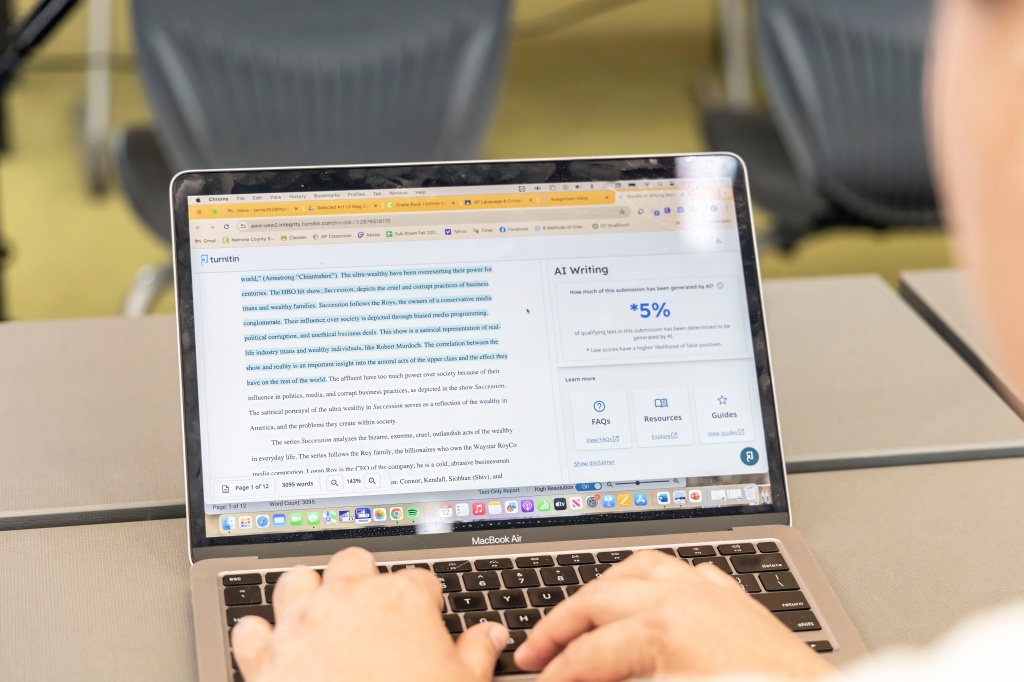

Many different websites are available for teachers to use to “detect” AI generated material. GPTZero, Crossplag and Turnitin are just a few that teachers can use. The problem, and it is a very big problem, is that these platforms are largely unreliable and inconsistent. Rarely do all of the sites agree on the percentage of AI generated content in any given composition. And then to make matters worse, there is the very real chance of false positives in AI detection. Compositions that were completely written by a human can be flagged as AI generated.

Jamie Tipps teaches AP Language and Creative Writing at KW. She has been frustrated with the lack of consistency in the detection tools. So far, no platform completely agrees on the content she runs through the various detectors.

“The most frustrating part of trying to accurately detect AI generated work is that there is no way to accurately detect AI generated work. Short of having the student handwrite an essay in class, there is too much ambiguity to know for certain if they’ve used AI. The students’ ability to beat the system has far out stretched the ability of our tools to catch them.”

So, what are teachers supposed to do to ensure academic integrity? Artificial intelligence isn’t going anywhere. It is here to stay and to progress.

“To be clear, I know that AI is now part of our reality, and I do believe that it can make aspects of our lives more efficient. However, I want my students to develop critical thinking skills first, so AI is eventually just a tool— not something that supplants their ability to think and problem solve,” said Tipps.

Leave a comment